Restoring a Desert River: Tamarisk Removal on the Upper Verde River

Healthy River-

Verde means “green” in Spanish, and the Verde River has been characterized historically by the many emerald meadows that once graced the river’s 170 mile stair step descent from Chino Valley north of Prescott, Arizona to its confluence with the Salt River, 3,500 feet lower near Scottsdale.

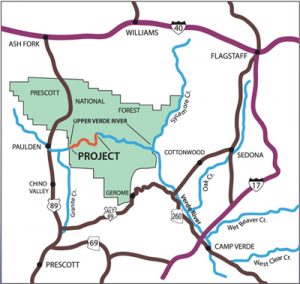

With headwaters just east of Paulden, Arizona the Upper Verde River comprises the first 33 miles of the 170 mile Verde River system, and most all of it crosses Prescott National Forest lands. The few remaining emerald meadows of the Upper Verde are populated mostly by sedges and play an extremely valuable role in armoring rich soils against erosion from intermittent floods.

The Upper Verde River is important to threatened, endangered and sensitive species such as native fish, including the spikedace and loach minnow. The river corridor is highly valued for recreation such as hiking, nature walking and kayaking. Quality water flow is vital to many downstream human communities within the Verde Valley and metropolitan Phoenix.

Invasive Woody Species-

Tamarisk, also known as saltcedar, is considered the worst invasive shrub impacting waterways in the Southwest. Scientific reviews note that tamarisk, allowed to expand, will dominate significant portions of riparian corridors and will negatively impact biodiversity and ecosystem functions. Tamarisk outcompetes native vegetation, causes major changes in riparian habitats, alters hydrologic and fire regimes, impacts wildlife habitats and soil biota, and consumes precious water. Tamarisk has not yet dominated the Upper Verde River ecosystem, but constitutes about 20% of the current woody plant density. Hence, a need was identified to remove and control tamarisk on the 12-mile headwater section, and restore functions and values to a native species dominated ecosystem.

Prior to 1993, woody vegetation was scant on the Upper Verde River. Streamside habitats were largely dominated by sedges and rushes, with occasional trees such as Arizona ash, walnut, and clumps of saltcedar, juniper, and other upland species. Today, the riparian habitats are comprised of dense, mixed stands of red willow, cottonwood, tamarisk, and upland woody species.

At their worst, tamarisk infestations alter the shape of the river and the way in which it functions ecologically. Channel downcutting and erosion of historical terraces are evidence of the encroachment effects of tamarisk in the floodplain. These processes lead to sedimentation and impairment of water quality. Tamarisk inhibits growth of sedges and grasses through shading. Sedges and grasses are important not only for catching and depositing sediment, but also for protecting the streambank from flood scour. Sedge-rush meadows provide diverse habitats for native wildlife and fish. Additionally, the meadows act as sponges to collect ground water, purify it and release it slowly back into the stream.

Tamarisk Removal-

Due to the difficulty of killing tamarisk root systems, trained professionals must cut stems close to the ground and immediately apply specific herbicides. In 2007 the Arizona Water Protection Fund issued a three-year grant to EcoResults Institute to administer tamarisk removal

on the upper most 12 miles of the Upper Verde River on Forest Service lands. EcoResults employed skilled technicians seasonally from the National Park Service’s Lake Mead Exotic Plant Team and Coconino Rural Environment Corps to do the work. The work was supervised by the Prescott National Forest and Rocky Mountain Research Station in accordance with stipulations of the 2004 Environmental Impact Statement for Integrated Treatment of Noxious or Invasive Weeds on the Prescott Forest. Garlon and Habitat were the herbicides used for this project.

Results-

Tamarisk stands were recorded by GPS, treated and then visited a second and third season to make sure any resprouting found was retreated. The project was professionally monitored at eighteen permanent transects to determine change in species diversity and at eighty photo sites to determine treatment effectiveness.

The river experienced major floods during each of the three years of treatment, which caused significant erosion and change to portions of the river bottom. Of the 9,884 live tamarisk stems documented on 80 study sites at the start of the project, only 118 live stems appeared after final treatment, for a 98.8% stem eradication rate. Permanent transect vegetation monitoring showed the only change in plant diversity was the almost total elimination of tamarisk.

Success Tips-

Careful planning is a requisite of tamarisk control project. Three to four years of project time allows time for the complete initial removal and treatment of massive stands, time to see which stands exhibit resprouting, and time to do required re-spraying.

Factors that bring successful results include:

- Inventorying all invasive plant species and doing GPS mapping of all stands.

- Monitoring from many sites with photographs that will document changes from treatment, flooding and weather.

- Obtaining necessary access approval in advance to facilitate crew and materials transport.

- Planning that avoids rainy and flooding periods, allowing a 20% downtime cost estimate for delays.

- Removing flood debris from stands and then cutting stems close to ground level.

- Cutting and treating plant stems when they are actively growing.

- Treating plants when temperatures are not so hot that herbicide vaporizes.

- Re-spraying 1.5 to 2 years after initial treatment to allow enough time to detect surviving plants.

- Stacking cut stems in piles on benchlands or lodged between native brush and trees to benefit wildlife.

Education & Outreach-

Our outreach program has contacted people of diverse ages and backgrounds in the local, regional and national communities to make them aware of the existing invasive plant conditions and their threats to sustaining diverse and productive riverine and wetland habitats in the Upper Verde River.

- Presentations were given at Chino Valley Heritage Middle School, Northern Arizona University, University of Arizona, and regional and national tamarisk conferences.

- Peer-reviewed publications were published in scientific journals, and an MS Thesis was completed at NAU.

- Field tours were given to the public and agency staffs, and information meetings held with the Arizona Game and Fish Department and environmental organizations.

- Newspaper articles were featured in local papers and this brochure is being distributed regionally.

Partnerships-

The success of this project exemplifies how private organizations can assist land management agencies to achieve land restoration goals for the long-term benefit of Arizona’s communities. This project was a cooperative undertaking led by EcoResults Institute (www.ecoresults.org) and the Arizona Water Protection Fund Commission, with technical assistance from the U.S. Forest Service Prescott National Forest and Rocky Mountain Research Station, Flagstaff, Arizona. Pioneer taramisk removal on the Y-D Ranch and Verde River Ranch inspired the project. On-site work was performed by the Lake Mead Exotic Plant Management Team and the Coconino Rural Environment Corps.

Open meadows can be invaded by trees that disrupt normal river functions.

Large tamarisk stands crowd formerly open meadow areas.

(1) LMEPMT crew cutting tamarisk and spraying stems with Garlon. Debris removal to uncover stems is a major work effort required to assure effective tamarisk kill and floodplain restoration. (2) One crew member records GPS data while another sprays cut tamarisks stems.

Same tamarisk stand shown before and after treatment.